Need

A common task in computational biology is the creation of protein graphs to convey an idea. These ideas can range from showing molecular complexities of diseases [1] or general layout of cellular components [2]. However, this is sometimes a complex task that can take a significant amount of time for an expert to complete. In previous work, the Crowd Intelligence Lab at VT has shown that crowdworkers on Amazon Mechanical Turk can create and evaluate this kind of graph. However, the field of citizen science (like the projects on Zooniverse [3]) has the potential to also be a good source of evaluation, which can allow a refinement feedback loop to create better graphs.

Approach

As previously mentioned, Zooniverse is a website that collects, hosts, and promotes citizen science projects. In addition, they have a good project wizard that helps budding project managers to easily get projects up and running. Therefore, I have taken a collection of 78 layouts in .jpg format and uploaded them to Zooniverse. Then, citizen scientists will execute a workflow that evaluates the graph along several metrics and prompts for qualitative feedback. A picture of the interface can be seen below.

Benefit

This project aims to benefit biologists and related experts through giving them a tool to enhance and evaluate generated graphs. This tool should quickly give feedback on issues of aesthetics and readability, which will strengthen any argument they are trying to make with the graph. Furthermore, citizen scientists are performing analysis on these projects for intrinsic benefits rather than extrinsic benefits (like getting paid). Previous work has shown that difficult tasks are performed more precisely by citizen scientists than crowdworkers [4], which would should benefit this task.

Competition

Competition comes from many places for crowdworkers in this field. Currently, there are 69 projects hosted on Zooniverse alone; each citizen science project vies for workers to analyze their data. Furthermore, this competes with the traditional methods of the expert just laying out the graph themselves and refining as needed. Some data is proprietary or has other needs to be kept private, so not all biologists will think this is an effective tool. Lastly, the CrowdLayout tool that was developed previously also competes; getting a crowdworkers to layout graphs in minutes is fairly effective.

Results

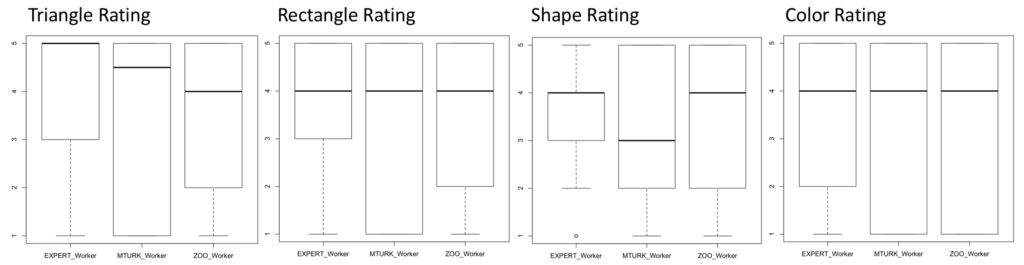

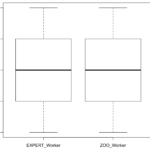

Due to Zooniverse’s requirements on projects they promote, this experiment was unable to get to their main page. However, 161 responses were gathered after promotion via emails and flyers. Of these responses, 24 were discarded due to being incomplete answers. Quantitatively, the results are statistically similar after performing Mann-Whitney U-tests on each metric and the overall rating. Seen below are the boxplots of the data, showing that the averages and confidence. Qualitatively, I found that 62 of 119 responses (18 did not provide qualitative feedback) were constructive. This was described as containing some sort of placement or edge suggestions. Furthermore, there was evidence of problems with the interface (7 responses), malicious users (11 responses), users who didn’t understand the task (8 users), and issues specifically with edge crossings (12 responses).

Overall

Discussion

Zooniverse’s interface and wizard can create a tool that allows for graph evaluation at a similar effectiveness as paid crowdworkers. Furthermore, the workers created action items in the form of constructive feedback in 52% of ratings. It was also odd to see malicious responses (as defined by Gadiraju et al. [5]), since these are volunteer-based studies. In addition, the hurdles that Zooniverse has for promotion on their website makes it difficult to serve as a permanent solution unless the throughput and graph generation increases.

Citations

- Baraba ́si, A.-L., Gulbahce, N., and Loscalzo, J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nature Reviews Genetics 12, 1 (2011), 56–68.

- Barsky, A., Gardy, J. L., Hancock, R. E., and Munzner, T. Cerebral: a cytoscape plugin for layout of and interaction with biological networks using subcellular localization annotation. Bioinformatics 23, 8 (2007), 1040–1042.

- https://www.zooniverse.org/

- Mao, A., Kamar, E., Chen, Y., Horvitz, E., Schwamb, M. E., Lintott, C. J., and Smith, A. M. Volunteering versus work for pay: Incentives and tradeoffs in crowdsourcing. In First AAAI conference on human computation and crowdsourcing (2013).

- Gadiraju, U., Kawase, R., Dietze, S., and Demartini, G. Understanding malicious behavior in crowdsourcing platforms: The case of online surveys. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM (2015), 1631–1640.