Paper:

Bica, M., Palen, L., & Bopp, C. (2017). Visual Representations of Disaster. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 1262–1276). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Discussion Leader:

Tianyi Li

Summary:

This paper investigated the representation of the two 2015 Nepal earthquakes in April and May, via images shared on Twitter in three ways:

- examine the correlation between geotagged image tweets in the affected Nepali region and the distribution of structural damage

- investigate what images the Nepali population versus the rest of the world distributed

- investigate the appropriation of imagery into the telling of the disaster event

The authors combined both statistical analysis and content analysis in their investigation.

The first question aims to understand if the photos distributed on social media correlates to the actual structural damage geographically, and if such distribution can measure the disaster accurately. They found that the distribution is significantly correlated statistically, however, a more in-depth analysis revealed that the geotags mean relatively little in relation to the finer aspects of geography and damage in Nepal: the images are less frequently photos of on-the-ground activity, and more frequently infographics and maps that originate from news and media.

The second question aims to understand how local and global audience perceive and relate to the disaster. They defined the boundary between “local” and “global” by the usage of Nepali, and pided the tweets into two dimensions: time (after first vs. after second) and geolocation (local vs. global), resulting in four categories (globally-sourced-after-first, globally-sourced-after-second, locally-sourced-after-first, and locally-sourced-after-second). The analysis results from hand-coding the Top 100 most retweeted image tweets in each of the four categories show a different diffusion of content, with locals focusing more on the response and the damage the earthquake caused in their cities, and the global population focused more on the images of people suffering. After the second earthquake, the results suggest some disaster fatigue for those not affected by the events and celebrity attention becomes the new mechanisms for maintaining the world’s gaze upon Nepal.

The third question studies the two competing expectations: journalistic accuracy and drawing a collective gaze of photography. They found four images in the full dataset of 400 image tweets that were confirmed to be appropriated from other times and/or places in globally-sourced-after-first, and an additional image in locally-sourced-after-first that has ambiguous origins. The fact that those images are appropriated is acknowledged either through replies or the originaltweets “as an honest mistake”, as “another way of visually representing disaster and garnering support through compelling imagery”.

Reflections:

This paper investigated imagery contents on tweets about the two earthquakes in Nepal in 2015, as a example to analyze disaster representation on social media. I appreciate the thorough analysis taken by the author. They looked at the tweets with image contents with three different research questions in mind, and studied different dimensions of such tweets as well as their correlations: between geotags and contents, between local and global audiences, and between actual pictures of the disaster and appropriated images from other time and/or locations.

Their analysis is comprehensive and convincing, in that they combine complete and strong statistical analysis and in-depth content analysis. This well structured analysis revealed that despite the strong statistical correlation between geotags and images, the pictures posted are mostly infographics from news media which doesn’t really tell much about the “objective” depict of the on-the-ground situations of those affected places. It is a good example of the importance of content analysis and future researchers should not settle with superficial statistical phenomena and should try to look at the data closely.

Especially, I found their way of defining the boundary of local vs. global by language smart. In spite of the acknowledged limitation mentioned in the paper, languages can effectively distinguish the audience of the tweets. Taken into consideration that Nepali is the only official language, it’s an efficient and smart way of taking advantage of this.

Questions:

- Do you agree with the authors that “…therefore, to watch is to witness. It is a responsibility to watch, even when watching is nevertheless entangled with problems of objectification and gratitude for not being a victim oneself.” is true in a global, geographically distributed online community? In other words, what do you think of the value of a “collective gaze” in the Internet era?

- What do you think of image appropriation? Is it acceptable to draw wider range of attention from a broader, global community, or is it journalistically inaccurate and irresponsible thus not acceptable?

- What do you think of the authors’ way of distinguishing “local” and “global” via language? Can you come up with a better boundary?

- In their hand-coded categories of tweet contents, they acknowledged that “relief & recovery rescue” also contains “people suffering”. Why do they not merge these two categories? What do you think of their coding schema?

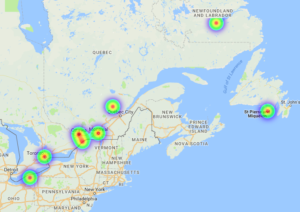

either link. Let’s look at the HeatMap first. The slide bar is to adjust display thresholds. If we zoom in, we can see protests occurred in Southern Ontario, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, outside Quebec City and even some in Newfoundland and Labrador.

either link. Let’s look at the HeatMap first. The slide bar is to adjust display thresholds. If we zoom in, we can see protests occurred in Southern Ontario, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, outside Quebec City and even some in Newfoundland and Labrador.