Review:

Niculae, Vlad, et al. “Linguistic harbingers of betrayal: A case study on an online strategy game.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.04744 (2015).

Summary

The authors are trying to find linguistic cues that can signal revenge. To this end, they use online data for a game called “Diplomacy”. The users are anonymous. The dataset is ideal in that friendships, betrayals and enmities are formed and there is a lot of communication between the users. The authors are interested on Dyad communications, between two people. Subsequently, this textual communication might provide some verbal cues for an upcoming betrayal. As the authors suggest, they do find that certain linguistic cues, such as politeness, leads to betrayals.

Reflections

I have never played the game and I had to read the rules in order to understand it. The research focus is on Dyad communication and betrayal. But are the conversations public, or private? Can the players see you communicating with someone? To get a better understanding I read the rules of the game and the answer is as follows: “In the negotiation phase, players communicate with each other to discuss tactics and strategy, form alliances, and share intelligence or spread disinformation about mutual adversaries. Negotiations may be made public or kept private. Players are not bound to anything they say or promise during this period, and no agreements of any sort are enforceable.”[1]. Subsequently, there is an extra layer of choice besides communication, on whether the negotiations are private or public. These choices might be not captured on Dyad communications.

The authors make a serious point with respect to game theoretic decision making models that attempt to model decision making and interactions. However, I believe that the approach of the authors and the game theoretic approaches are complementary and do not necessarily contradict each other. “Decision theory” is a highly abstract, mathematical, discipline and the models are rigorous in the sense that they follow the scientific method of hard sciences. In addition, just for clarification, the vanilla Prisoners Dilemma is not a “repeated game” as the authors stress. It can’t be formulated as a repeated game however the Nash Equilibrium changes when that happens. Something that should be stressed is that this is not a “repeated game”. The online game was not repeatedly played with the same players over and over again. Had the players played the game repeatedly, eventually they might have changed their behavioral strategies. This in turn might have affected the linguistic cues. In game theory, repeated games, as in games with the same agents and rules that are played over and over again, have different equilibria than static games. Subsequently, I am not sure if the method can be even generalized for this particular game, let alone other games where the rules are different for this reason.

Idiosyncrasy/rules of the game. Eventually, in order to win you need to capture all the territories. Thus the players anticipate that you might eventually become their enemy. This naturally has an impact on the interactions. In the real world, you don’t expect – at least me – to be surrounded by enemies who want to “conquer your territories”. The game induces “betrayal incentives”. If we design the game differently, it is likely that the linguistic predictive features that signal “betrayal” will change. There is a field called “Mechanism Design” dedicated to see how changing the rules of a game yield different results (“equilibria”).

The authors focus on friendships that have at least two consecutive and reciprocated acts of friendship. Should all acts of friendship count the same way? Are some acts of friendship more important than other acts? In other words, should there be a “weight” on an act of friendship?

The authors focus on the predictive factors of betrayal. I wonder, how can we use this in order to inform people on how to maintain friendships. The article makes an implicit assumption that friendships necessarily end due to betrayals. This is natural, because these terms used in the content of “Diplomacy” (the game). In the real world, there could many reasons why friendships can end. It would be interesting to develop a predictive, behavioral, algorithm that predicts the end of friendships because of misunderstandings.

The authors are trying to understand the linguistic aspects of betrayal and as a result, they do not use game specific information. However, if this information is not taken into account, then it is likely that the model will be wrong. By controlling for these effects, we can have a clearer picture of the linguistic aspects of betrayal.

Questions

- What if the players read this paper before they play the game? Would this change their linguistic cues?

- Should all acts of friendship count the same way? Are some acts of friendship more important than other acts?

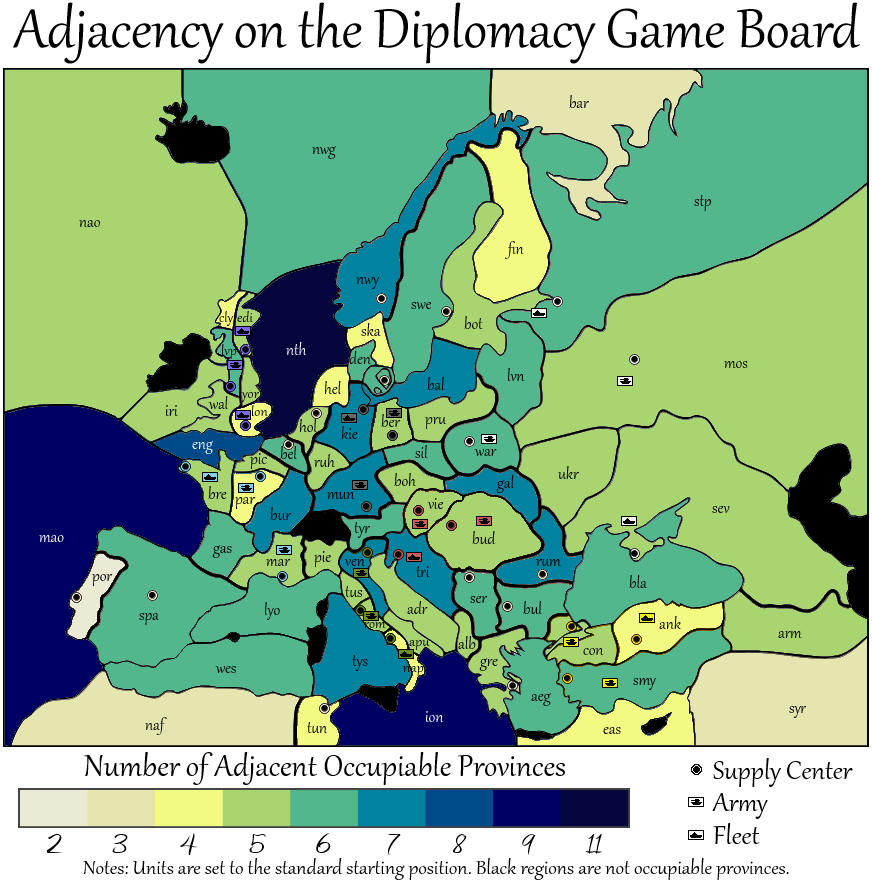

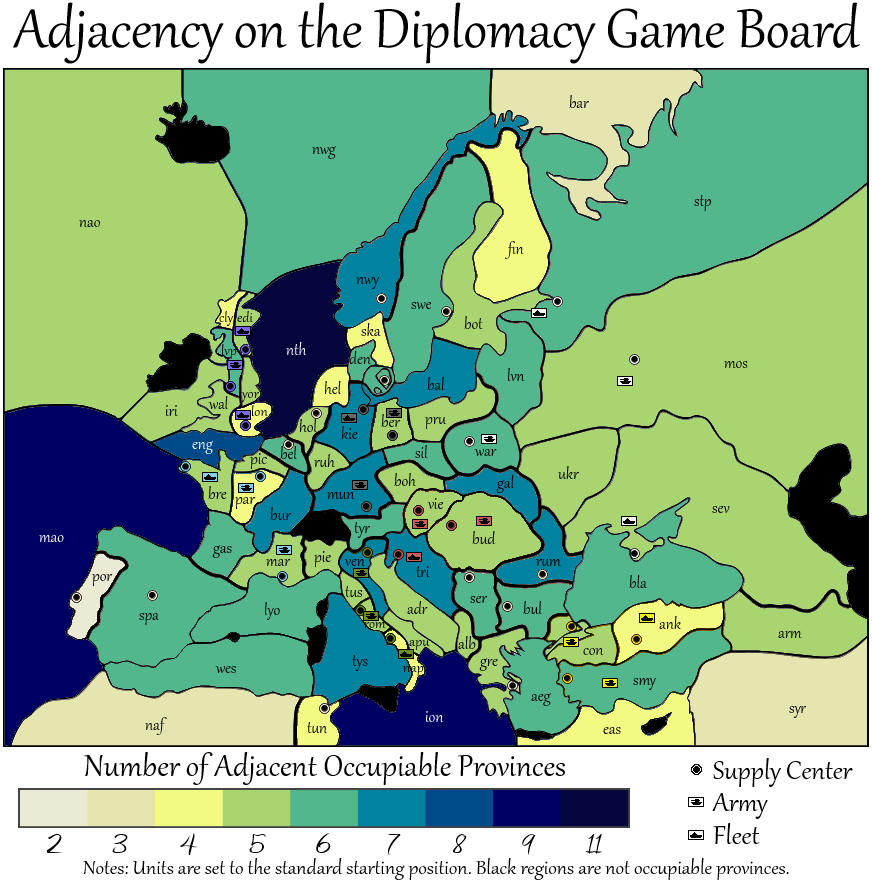

- What if the authors did control for game specific information as well? Would this alter the results? Based on some models for the same game, it seems that if you select some countries, you will ultimately have to betray your opponent. For instance, “adjacency” is apparently an important factor that determines friendships and enmities. An adjuscency map can be seen in the attached map.[2]

- What if the users knew each other and played the game again and again, rendering the game repeated? Would this change the linguistic cues, after obtaining information regarding the behavioral patterns from the previous rounds?

- Can players visually see other players interacting and the length of that interaction? What if they can?

[1] Wikipedia

[2] http://vizual-statistix.tumblr.com/post/64876756583/i-would-guess-that-most-diplomacy-players-have-a

Read More