- King, Gary, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts. “Reverse-engineering censorship in China: Randomized experimentation and participant observation.” Science6199 (2014): 1251722.

- Hiruncharoenvate, Chaya, Zhiyuan Lin, and Eric Gilbert. “Algorithmically Bypassing Censorship on Sina Weibo with Nondeterministic Homophone Substitutions.” ICWSM. 2015.

The first paper presents a large-scale experimental study of Chinese social media censorship. The authors created accounts on multiple social media sites and submitted various texts, while observing which texts get posted and which get censored. The authors also interviewed employees of a bulletin board software company and other anonymous sources to get a first hand account of the various strategies used by social media websites to censor certain content. This approach is analogous to reverse engineering the censorship system; hence the title of the paper is appropriate. The key hypothesis that this study tries to prove is that of collective action potential, i.e. the target of censorship is people who join together to express themselves collectively, stimulated by someone other than the government, and seem to have the potential to generate collective action in the real-world [How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression.].

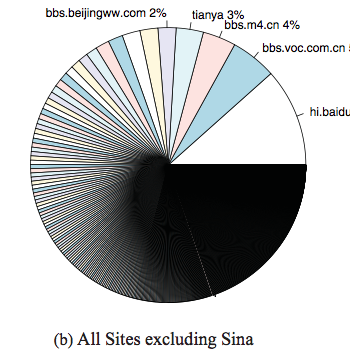

Overall, I find the paper to be an interesting read and Figure 1 gives a nice overview of the various paths a social media post can take on Chinese discussion forums. The authors find that most social media websites used hand-curated keyword matching for automatic review of user posted content. The most interesting fact was that large Chinese social media firms will be hiring 50, 000 to 75, 000 human censors and Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda department, major Chinese news websites and commercial corporations had collectively employed two million “public opinion analysts” (professionals policing public opinion online) as early as 2013 [1]. This implies that for every 309 Internet users in China there was one human censor (There were approximately 618 million Internet users in China in 2013) [2]. With regards to the histogram presented in Figure 4, other than the reasons presented in the paper for the high number of automated reviews on government websites, it may be the case that these websites might be getting a lot more posts then private websites. I believe a large number of posts, would lead to a greater number of posts being selected for automatic review. Additionally, if a person has an issue with a government policy or law, trying to publish their disagreement on a government forum might seem more appropriate to them. Now, given the fact that phrases like: change the law (变法) and disagree (不同意) are blocked from being posted, even on Chinese social media sites, I believe any post showing concern or disagreement with a government policy or law on a government website will be highly likely to be reviewed. Moreover, given the long (power-law like) tailed nature of Chinese social media (as shown in the pie chart below from [King et. al. 2013]), I feel majority of the small private social media websites would be acting as niche communities (e.g., food enthusiasts, fashion, technology, games) and it is unlikely that individuals would post politically sensitive content on such communities.

The second paper discusses an interesting approach to evade censorship mechanisms on Sina Weibo (A popular Chinese microblogging website). The authors cite the decision tree of Chinese censorship from the first paper and highlight the fact that homophone substitution can be used to evade keyword based automatic review and censorship mechanisms. The paper details a non-deterministic algorithm that can generate homophones for sensitive keywords that maybe used to filter microblogs (weibos) for review by censors. The authors prove that the homophone transformation does not lead to a significant change in the interpretability of the post by conducting Mechanical Turk, Human Intelligence Task experiments. The key idea here is that if the censors try to counter the homophone transformation approach by adding all homophones for all blocked keywords to the blocked keyword list, they would end up censoring as much as 20% of the daily posts on Sina Weibo. This would be detrimental for the website as this implies loosing a significant amount of daily post and users (if the users are banned for posting the content). The authors suggest that the only approach which would work to censor homophone transformed posts, while not sabotaging the websites daily traffic would be to employ human censors. This would impose 15 additional human-hours per day worth of effort on the censors for each banned word, which is substantial as there are thousands of banned words.

In Experiment 1, the authors stopped checking status of posts after 48 hours, a question I have is that do all posts ultimately get read by some human censor? If this is the case, is there a justification for the 48-hour threshold to consider a post as uncensored? As the authors suggest in the study limitations, posts by established accounts (specially those having a lot of followers) might be scrutinized (or prioritized for review/censorship) more. It would be interesting to see if there exists a correlation between the number of followers an account has and the time at which their sensitive posts get deleted.

Furthermore, in the results for Experiment 1, the authors specify that there is a statistically significant difference between the publishing rate of the original and transformed posts, in terms of raw numbers, we don’t see a huge difference between the number of original (552) and transformed (576) posts that got published. It would be interesting to repeat Experiment a couple of times to see if these results remain consistent. Additionally, I feel we might be able to apply a Generative adversarial network (GAN) here, with a generator generating different transformations of an original “sensitive” weibo which have high interpretability although can fool the discriminator, the discriminator would act like a censor and decide whether or not the generated weibo should be deleted. Although, I am not sure about the exact architecture of the networks or the availability of sufficient training data for this approach.

Addendum: An interesting list of terms blocked from being posted on Weibo.